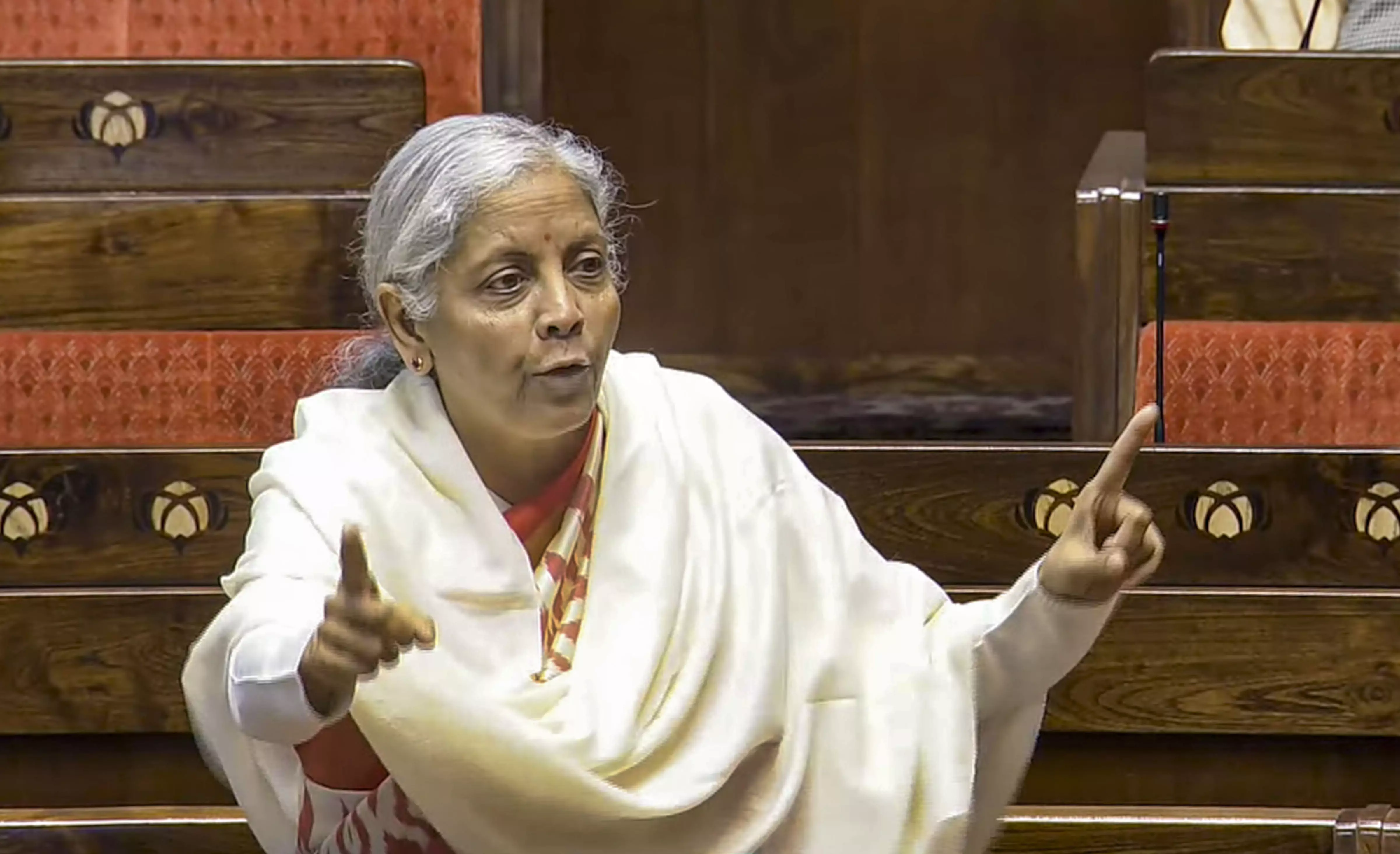

While many taxpayers are busy planning for the end of the year and the new year this coming week, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman and her colleagues are adding numbers to the budget statement and finalizing the speech on February 1. Budget numbers and key proposals should be in the pipeline by early January after the Prime Minister gives his imprimatur, with the speech itself going through several drafts until the final days. What the government does and can do depends largely on the numbers.

The Narendra Modi government’s annual budget speech has stuck to a pattern for years. Half of the speech is devoted to claiming all the good works and the other half is offered. Much less attention has been paid to the actual content of the annual financial statements presented to Parliament, why the revenue estimates deviated from the budget estimates and the impact of various proposals on the expenditure side and the revenue side.

The actual scrutiny of the budget is left to analysts who spend the next few days analyzing the budget proposals. After all, few are interested in anything more than what tax proposals mean for their household budgets. All the big plans and proposals are meant to be sold by party spokespersons in prime time. With the introduction of goods and services tax, the annual budget speech has lost its usual excitement as everyone waits to find out how much the price of soap or cigarettes will be.

While there has been little dramatic action on the direct tax side during Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s tenure, after the changes made by former Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, some headline-grabbing changes are expected this year. Middle-class wage earners expect some relief in direct taxes and there is talk of some burden on the super rich and wealthy.

Speculation about the latter comes as ministers and officials add their voices to the voices of many analysts who are concerned about the widening income gap between the rich and the middle class and its impact on consumer behavior. In the first quarter of the financial year 2024-25, the decline in the sale of consumer durables and non-durable goods and the slowdown in the national income growth rate have sounded alarm bells in boardrooms and government offices.

National accounts data for the past decade show that total private final consumption expenditure, a fairly good proxy for income, grew at an average annual rate of 6.0 percent over the period 2013-2023. However, household spending on education (7.5%) and healthcare (8.2%) grew faster than spending on consumer goods, food and fuel. Clearly, the increasingly private provision of both health and education has become a pain point for middle-class families. As job growth slows, many middle-class income earners have to spend more within their households to support both the unemployed youth and the retired elderly.

In her July interim budget speech, the finance minister listed what she called “next generation reforms”. Most of these, such as reforming land records, establishing land registries, mapping land ownership and digitizing cadastral maps, are mainly under the purview of state governments. Apart from references to climate finance and the rupee, little attention was paid to what the Center could do. There are many things the central government can do to improve the “ease of doing business”.

without this effort. Private investment will not respond as Ms Sitharaman had hoped.

Despite all this, expect Ms. Sitharaman to begin her speech with an “Amrit Kaal” painting a glorious picture of how India is on its way to becoming a “developed India”. With a growth rate of 6.5 percent, much can be said about the fact that India’s economy is one of the fastest growing economies in the world and is on the verge of becoming the third largest economy in the world after the US and China. Arguments for sustainable growth over the past quarter century would certainly ensure this, but today’s major concern is the quality of that growth process and what it means for the middle class and the poor.

Even about the growth numbers, there is an issue. It is now widely accepted, within the central government, by research institutions and multilateral financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, that India’s medium-term growth rate may be around 6.5 percent. While optimists expect it to be 7.0 percent, critics and pessimists don’t see it surpassing 6.0 percent. This is the state of the numbers debate today. How should it be viewed?

Consider the fact that after recording an average annual growth rate of 5.5 percent in the two decades from 1980 to 2000, the Indian economy grew at an average of 7.5 percent during the period 2000-2012, with annual growth peaking at over 8.0 percent. Percentage in 2003-2009.

I remember industrialist Mukesh Ambani giving a presentation to Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee around 2000 in which he showed how the economy could aspire and achieve an annual growth rate of 10 percent. Such optimism no longer exists.

In the report submitted to the government at the same time in 2000, the then National Security Advisory Board said that the economy should maintain a growth rate of 7.0 to 8.0 percent to raise sufficient income and financial resources for poverty alleviation. Arranging public investment in job creation, health, education, research and defense. I imagine this would still be true today.

Therefore, the challenge for the central government is to bridge the gap between the widely expected medium-term growth rate of 6.0 to 6.5 percent and the required 7.0 to 8.0 percent. How does Ms. Sitharaman propose to add that extra one percentage point increase to her next year’s budget and fiscal proposals?

Instead of getting breathless and thirsty with long speeches full of glory and thunder, let’s hope the finance minister shows us a planned path from good to great performance.